More about the Sites of Roman Bonn

Replica Roman Street Lined with Tombs in Rheinaue Leisure Park

Rheinaue Park, a central leisure park in the former government quarter near the United Nations Campus and the Museumsmeile, was created for the Federal Garden Show (Bundesgartenschau) in 1979. The local archaeological museum, the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn2, contributed the publicly accessible Roman street with replicas of Roman tombstones and votive stones found in Bonn or the Germania inferior3 (the Roman province). Although the stones had never been arranged in the same way as the replicas in Rheinaue now, they provide an interesting potpourri of people who lived, worked and traded in the area of the Rhineland. Some stones mention slaves and their partners4, soldiers who died in important battles, natives who adopted Roman traditions or local deities5 worshipped by the local and Roman population.

Roman Baths in the Basement of Marriott Hotel

In 2006, the City of Bonn and an investor decided to build the World Conference Center Bonn (WCCB)6. During the construction works the ancient remains were discovered and partly moved with a heavy lift crane in 5 blocks of max. 160 tonnes each, 50 metres away to what is now the spa area in the basement of the Marriott Hotel (see its contruction here7, 00:10–01:28). It is now open to the public during opening hours.

Baths are not only a sign of the strong Roman influence – they invented and perfected bathing culture – but also of social life and pleasure. They were open to the inhabitants of the vicus8, children, women9, slaves, masters, etc. Apart from the hygienic effect, the baths will have lowered the barriers between the social classes, as they met in such places.

Tip: Play the video beamed onto the wall above the remains.

Basement of a Roman Tavern

This basement of a Roman tavern was discovered and excavated in 2006, when work began on the construction of the Museum of Modern History, known as the "Haus der Geschichte10". The remains date back to the 2nd century AD and were left in situ, that is, where they were originally found. The cellar belonged to a so-called "strip house11", an elongated house of about 10 x 30 metres, with one side open to the street to sell articles or food manufactured in the workshop behind. Several interesting archaeological finds have been made in the area of the tavern, illustrating the daily, religious, family (and even criminal) life of the people. Like the public baths12 the tavern was part of the vicus of Bonn.

Roman Baths (Administrative Military Unit)

These baths have raised some questions for archaeologists because their context is uncertain. They belonged either to a special military office or to an administrative office. Accommodation and another bath were found nearby, probably used by the soldiers of the military office. The baths here were assigned to the commander. The sections of the bath were visited in a certain order: After the changing room (apodyterium), visitors used the cold bath (frigidarium), the warm bath (tepidarium), the hot bath (caldarium) bath, and, if there was one, the sweat room (sudatorium). Another room with a staircase can be seen, which was once filled up with construction waste to enlarge the changing room. As the baths were certainly used for political purposes, and as the Bonn garrison13 grew in importance, the modification of the building was probably the commander’s wish to have more room to meet with other important people.

The replica of the statue of Mercurius 14testifies to the importance of the commander whose slaves/freedmen donated the stone. The god of trade, travellers and thieves can be recognised by his rod (caduceus), winged shoes (talaria), winged hat (petasos), a purse and the turtle at his feet.

Inscription: Mercurio / Noihus et Noiius / L(uci) Vibi Visci Macrini / leg(ati) Aug(usti) v(otum) s(olverunt) l(ibentes) m(erito) –15 "To Mercurius, Noihus and Noiius, slaves/freedmen of the governor Lucius Vibus Viscus Macrinus happily and gratefully redeemed their promise."

Trachyte Blocks from Ancient Monumental Building in Front of Bonn Minster

The cult of the Matronae5 was spread throughout the province of Germania inferior3 (and even further). The center of this cult (or branch, e.g. the Matronae Aufaniae) was probably in Bonn, but the main temple hasn’t been found yet. Some people think that, since churches were often built on ancient sacred sites, this must have been beneath Bonn Munster16. In 1928, a cella memoriae, a late antique place of worship with a bench and an altar, was found there, (which would become the focus of a Saints’ Cult dedicated to the Diocletianic martyrs Cassius and Florentius). For this reason, some researchers believe that the architectural remains found under the cathedral belonged to the main temple of the Matronae. The bronze tablets17 were added later, in 1979, and depict important scenes from the life of St. Martin of Tours.

Small Relic of a Roman Wall

This barely perceptible piece of Roman wall may be unimpressive, but its location between the vicus, the auxiliary camp, the canabae and the legionary camp is indicative of Bonn’s importance8. The areas merged or were reused, and the population of the north-south axis on the Rhine was a vibrant one throughout the centuries of Roman occupation. The growth, success and prosperity of the canabae and the vicus of Bonn were nourished by and dependent on the road linking Tier (Augusta Treverorum) and Cologne (CCAA – Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium).

Reconstruction of a Roman Baking Oven

This oven was excavated in 1995 during the construction of the current building for the Stadtwerke Bonn18 on Welschnonnenstraße, at the edge of the Canabae Legionis19, the civilian settlement8 directly outside of the legionary fortress walls13. This excavation discovered four so-called-strip houses, half-timbered constructions with narrow street frontages, used as shops or workshops with living quarters at the rear, which were typical for the north-western provinces. Those found on Welschnonnenstraße have been dated to the third century by a brooch found in the excavated layers of the site. The houses contained a bone-processing workshop, a butcher’s and a kitchen which featured the baking oven, as well as cooking pits. This kitchen probably belonged to a fast-food establishment, common in the Roman world where few people outside the elite had access to individual cooking facilities. Up to five kilos of bread per hour could be baked in the oven, and rooms adjacent to the kitchen contained hypocaust heating systems20 – perhaps to preheat unbaked loaves, or keep patrons comfortable. At some point in the later third century, a destruction layer suggests this house burned down. This may have been due to a Frankish invasion of the Rhine frontier in 274 A.D., or to an unknown event, as it remains difficult to relate archaeological evidence for destruction to historically attested developments. The oven on display is a reconstruction, using its original components, by the Rheinische Amt for Bodendenkmalpflege, Außenstelle Overrath.21

Auxiliary Camp

The auxiliary camp, which pre-dates the legionary fortress 22and was present in Bonn between 17–43 C.E., housed soldiers who would have been recruited from the Empire’s subject provincial populations who lacked Roman citizenship23. Before the twentieth century, its location was debated, but archaeological excavations in 1983 and 1987 at the Theaterarkaden and at the Dorint Hotel confirmed its location13. It was situated on a high bank above the Rhine between Josefstraße, Giergasse, and Belderberg, with a polygonal form (with at least 5 corners) and with a surface area of approximately five hectares. This camp would have housed both an auxiliary unit on horseback, the ala Frontoniana, and a standard infantry cohort, the cohors I Thracum.

Stiftsplatz: Center of the Legionary Camp’s Suburb (canabae legionis)

In the Roman Empire, soldiers were not allowed to marry. However, they may have had families before joining the military, or they may have had families without marrying8. Since the Legio I Minervia was stationed in Bonn for about 200 years, families settled near the legionary camp13. This area, the so-called canabae legionis, had its center – the forum – in the area of the present Stiftsplatz. Remains of temples dedicated to various gods and goddesses (the Capitoline Triad24, Mercury, but also for the Matronae25) have been found here. Religious tradition was a central part of life in Roman antiquity, involving all levels of society, including the emperor, the paterfamilias (the head of a familia, which also included slaves), as well as female and male priestesses.

Southern Gate of the Legionary Camp (Crossing Rosental x Römerstraße)

The ancient southern gate of the legionary camp would have stood at the northern side of the intersection between Rosental and Römerstraße. The shape of the legionary camp can still be detected in Bonn’s road network, with Rosental, Graurheindorfer Straße, Augustusring and the Rhine forming what would have been its four sides13. The length of each side was about 524/526 metres. Many of the legionary camp’s remains are still underground, but the layout of the camp is well known, as the construction of Roman camps usually followed a standard outline (with gates, main axes, commander’s house etc.). The road along the Roman frontier (called the limes)26 followed the course of the Rhine. In the Bonn region, in order to avoid it crossing the legionary camp, it was rerouted along Kölnstraße27.

Near to the intersection of Rosental and Römerstraße, on the outside wall of the hotel "Am Römerhof", you can see a plaque donated for the 2000th anniversary of the city. The text reads: Senatus populusque Bonnensis – "The Senate and the people of Bonn", a reference to the Latin wording senatus populusque romanus – "The Senate and the Roman people".

Caesar Statue in Beuel-Schwarzrheindorf

Gaius Iulius Caesar extended the Roman Empire to the Rhineland and across the Rhine. He built several bridges across the Rhine in order to advance even further eastwards. It is uncertain whether he also built a bridge in Bonn (which, if he did, would have been a wooden bridge). In 1898, a statue of a seated Caesar was installed on the arch giving access to the bridge between Bonn and Beuel28. It got lost when this bridge was destroyed at the end of the second world war, in 1945. The statue was subsequently rediscovered and reinstalled during Bonn’s 2000th anniversary in 1989, this time on the right bank of the river at this location. It is a testimony to European reception of antiquity in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Caesar looks eastwards towards the land to be conquered. In his hand he holds the plans for the bridge. On the back of his chair is an inscription: C. IVL. CAESAR FLVMINI PONTEM PRIMUS IMPOSVIT A. A. CHR. N. LV – "Gaius Iulius Caesar was the first to build a bridge over the river in 55 B.C.".

Mosaic of Medusa at the “Rheinische Landesmuseum”

In 1904, two canal diggers found a stunning mosaic in the area of the legionary camp13. It had probably decorated one of the officer’s residences. Featuring the head of the Gorgon Medusa29 in the centre, surrounded by intricate black and white ornaments, it had a size of 3,4 x 2,8m and originated from the 2nd or 3rd century A.D. It was displayed in the "Provinzialmuseum" (today’s "Rheinisches Landesmuseum30") until 1944, when an aerial bomb hit the museum. The mosaic, which previously had lasted underground for 1600 years without any damage, was splintered into fragments. The museum staff first stored the remaining pieces away, but since 2023, the museum’s conservators have been trying to reconstruct the mosaic. Fortunately, before the bombing, a photograph of the mosaic had been taken which conservators are now using to reassemble the thousands of fragments. The reconstruction process is currently (May 2024) on public display at the Landesmuseum and can be viewed by visitors.

In the Roman world, Medusa’s face was not only used on mosaics, but also on amulets and other objects to ward off danger. This must have been the idea of the Roman officer who had this mosaic installed in the floor of his house.

Model of the Roman Legionary Camp

The model of the Roman legionary camp was built in 1989 to celebrate the 2000th anniversary of the city of Bonn. The names of the houses and buildings are given on the side of the model. Due to the dense development of the Castell district, not all areas of the camp could be excavated. However, by comparing the Bonn legionary camp with others, researchers have been able to reconstruct the unknown areas. Near the eastern wall were the granaries, which were larger than expected, so it is possible that they were used not only to feed the soldiers of the camp13, but also to store grain for the Lower Rhine region. Bonn would then have been not only a military base but also a commercial centre and supply hub for this entire section of the Roman frontier31.

Foundation Wall of Late Antique and First Christian Church (Dietkirche)

The legionary fortress was a focal point for settlement well into the early middle ages, as the Roman Empire's presence withdrew and Bonn came under control of Frankish military elites. In this context the medieval Dietkirche may have served as a parish church. An east-west facing church with three-aisled crypt has been present since at least the eleventh century A.D., but a hall whose purpose is unknown was already built in the Roman period. This was extended with a 10x20 m hall in opus africanum, a building technique which was relatively unknown in the Rhineland but widespread in North Africa, southern Italy, and Spain. Buildings of this type appear in north-western Europe in the fifth and sixth centuries, suggesting a post-Roman date32.

Much about life in Bonn during this early phase of the Dietkirche is unknown, but one clue might be an inhumation burial with grave-foods found within this structure. The deceased was likely an adult woman. The grave-goods included two bird-shaped brooches in gold-leaf and cloisonné decoration typical of the early sixth century. Scholars once believed that such finds evidenced the incoming Frankish population, but recent work has challenged this, arguing that such burials instead signal ideas about gender, the life-cycle, and the smoothing over of social tensions produced by the death of community figures33. The burial’s location is an uncertain clue that the building might have already been a church – it is similar to other Merovingian high-status church burials, such as those found beneath Paris St. Denis and Cologne Cathedral34. This also provides a likely context for the late antique burial ground found beneath the Aldi on Kölnstraße27. Early late antique churches were commonly built on pre-existing burial grounds.

Reconstruction of Roman Building Crane

The model for this crane is depicted on a Roman relief dating from 120 A.D. The crane was a gift from the City of Bonn to mark the city’s 2000th anniversary. Two men could fit inside the wheel and four more were needed to operate it. It could lift stones weighing several tons. Cranes like it would have been used to unload cargo from boats on the Rhine31, and construct the walls and other parts of the legionary camp. The Roman Empire’s feats of engineering are well known, and are most famously manifest in such monuments as the Colosseum, but were also crucial to the expansion of Roman urbanism and military domination.

Inscription: P(ublius) Roma/nius P(ubli) l(ibertus) / Modestus / annorum / XVI h(ic) s(itus) e(st)

Epitaph of an 16-year-old freedman named Publius Romanius Modestus, probably holding his manumission paper in his right hand.

Year of find: 1885, dating 31 AD–50 A.D.

Findspot: Bonn, Kölner Straße/Heerstraße

Present location: Bonn, Rheinisches Landesmuseum

Originally part of a column.

Depiction:

-

Iupiter on top as cosmocrat

-

Column: Iuno, Minerva, Mercury

-

Ashlar block: Hercules, Valeanus (?), Ceres, Mercury

Findspot: Bonn, Erkelenz, Köln-Weiden

Insciption: Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) / G(aio) Quint[o] / Messio / Decio / Traiano / Invicto / Pi[o Fel]ici / [Aug(usto)

Two parts of a column (middle part missing)

Findspot: Nettersheim (street Cologne-Trier)

Year of find: 1965, dating 249 A.D.–251 A.D.

Inscription: Matronis / Aufaniabus / Q(uintus) Caldinius Certus / l(ibens) m(erito)

Findspot: Bonn

The relief depicts a sacrificial setting for the goddesses (Matronae) sitting above the scenery. The man has his head covered (capite velato) and wears a toga, which are typical roman attributes. The woman wears a ubic garment and a necklace with a lunula pendant, which are typical local costumes. They seem to be a married couple who, with the help of their servants (small figures on the right and behind the altar) sacrifice the goddesses by burning incense.

Reconstructed Traces of the Aqueduct Leading to the Legionary Fortress (Yellow Ground Tiles)

A pipeline over 100 km in length carried water from the Eifel to Cologne, but Bonn sourced its water more locally, from two connected springs on the Hardtberg, probably because of the range of hills to the west. The tiles on the floor in this part of the city show the former route of the pipeline, which ended in the south-west corner of the legionary camp.

The supply of water has always been essential to human life. Smaller villages survived with cisterns or wells. The construction of a water conduit shows Bonn’s demographic and adminstrative significance beyond its status as a strategic military garrison35.

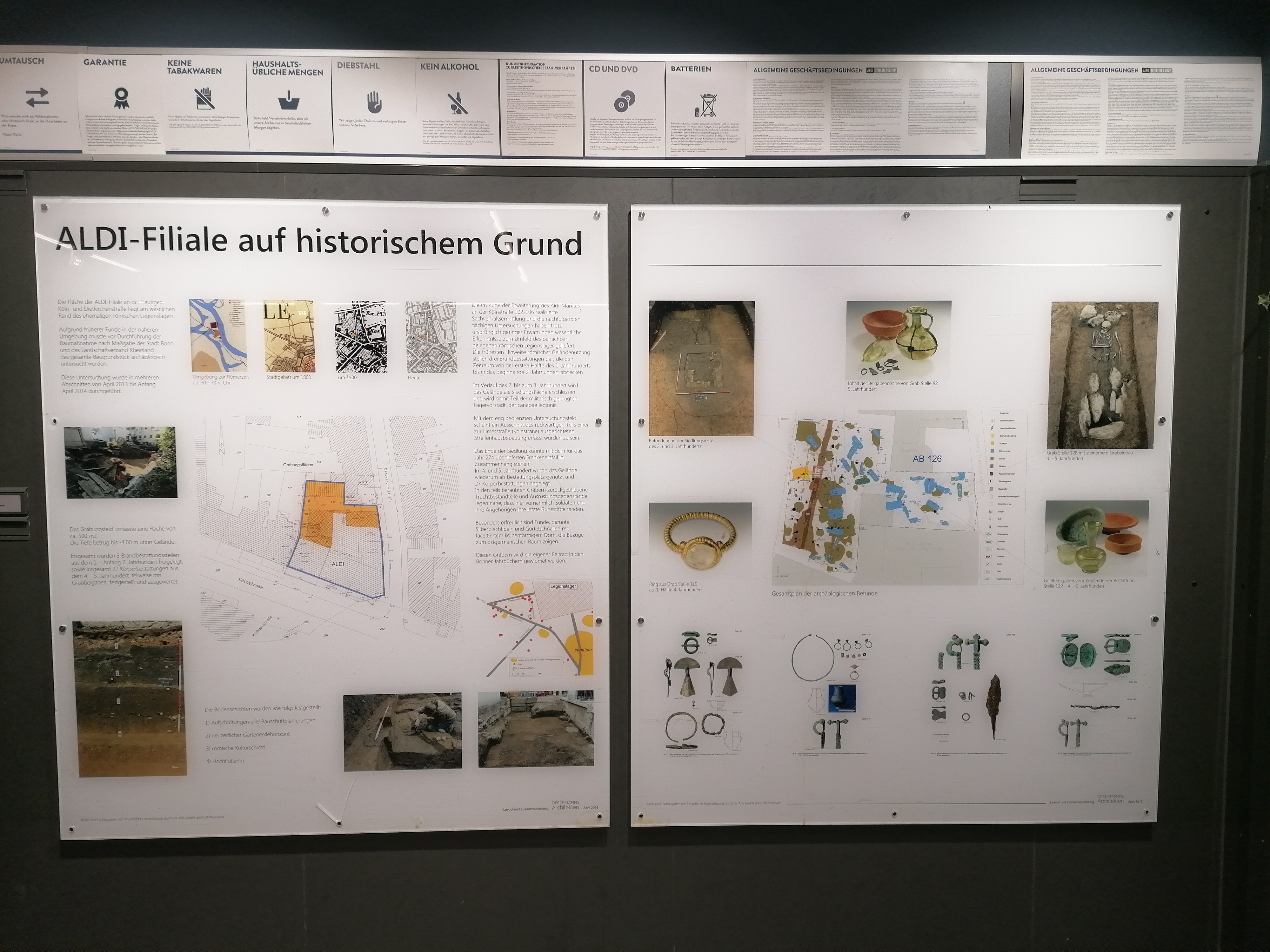

Aldi on Kölnstraße

The Aldi supermarket on Kölnstraße/Dietkirchenstraße was built over a Roman and late antique burial ground. In 2013-14, several valuable grave-goods were found alongside well-preserved bones, which are now on display at the Rheinisches Landesmuseum. The site reveals burial rites which vary considerably over time: the oldest burials (from the first century A.D.) are cremation burials, with the ashes being caught in a pit or collected and placed in an urn. In late antiquity, inhumation was the most common form of burial, and traces of wood indicate the use of wooden sarcophagi. Burial objects such as jewellery, bowls filled with food, coins or silver brooches36. One interpretation is that these were intended to help the deceased to have a good and fortunate afterlife. Other scholars have seen such practices as an expression of communal ties at moments of social crisis37.

Poppelsdorf Excavations

Despite Poppelsdorf's distance from the military camp13, the canabae legionis19 and the vicus,8 university archaeologists conducted here excavations (in 2012 and 2023) that brought exciting results. The area was once a rural centre with a large estate (villa rustica) and a Gallo-Roman temple8. In 2023, not only did a rare coin depicting a dancing little man come to light, but also an oven38, grindstones, storage pits and pottery fragments39; the latter could be even older than the ancient Roman remains. The Archaeological Institute of the University of Bonn40 used the site for educational excavations for its students. As the Poppelsdorf campus continues to grow, more excavations will be necessary, along with more ancient sites being built over.41

Pottery Workshop Complex at Bastion Sterntor

The old prison, built inside the ancient remains of the bastion, was pulled down in 1995 to make way for the extension of the Regional Court building42. Since the construction of an underfloor car garage was planned, the ground of the bastion was thoroughly explored, revealing 12 Roman pottery kilns.

The area was very marshy due to the branches of the river Rhine, a perfect location for pottery, where a water supply was essential and expedient for fire safety. When the legionary camp was established 13in the first half of the 1st century A.D., there was a need for pottery (pots, plates and other tableware). It is therefore very likely that the pottery at the Sterntor bastion supplied the legionary camp (and the surrounding canabae19) with ceramics.

Harbours on the Rhine Bank at the Fortress and the Canabae Legionis

Investigations of the geological morphology of the bank of the Rhine directly adjacent to the legionary fortress13 as well as frequent finds of Roman lead have prompted scholars to suggest that a landing point was likely present on the bank for the offloading of goods31. Those included the trachyte stone25 that would have been transported up the Rhine from the Drachenfels43 via the harbour in Königswinter.44

Further south, between present-day Vogtsgasse and Giergasse, archaeological excavations in 2010/11 discovered the remains of a Roman landing site at the southern edge of the Canabae Legionis19. This, and a suspected similar site at the vicus8, would have been a simpler affair – a dry stretch of shallow sloping gravel onto which ships could be dragged directly, and offloaded via cranes45. Archaeological investigations have suggested that the Romans intervened to fortify this bank, and that up to five ships would have been able to simultaneously land here.

The excavation also discovered the remains of a bronze figurine in the form of a lion, interpreted as a pocket "multitool", alongside two coins. One was a low-weight copper denomination depicting Faustina the Younger46, the wife of Marcus Aurelius; the other was a poorly preserved denarius minted in the reign of either Trajan47 or Hadrian48.

Harbour in Königswinter

At Königswinter, near Bonn, when the Rhine is very low, the old structures become visible, especially the landing place of the old harbour31. Quartz trachyte can be found in the range of hills known as the 'Siebengebirge50' ('seven mountains'). This volcanic rock was quarried by soldiers of the Legio I Minervia from Bonn13 and transported down the Rhine to Cologne and Xanten51. It was mainly used for inscriptions, but also for architectural purposes25. In later times, trachyte from Königswinter was used to build Cologne Cathedral52.

Structures in Kottenforst

The Roman military13 used the Kottenforst, a wooded area in the central western part of Bonn, as a training ground. More than 11 training zones from the first and second centuries have been found, recognizable by earth walls53. See laser images here54.

Road between Trier and Cologne

The Romans had a vast network of roads throughout their empire. Roman roads were an elaborate construction of layers of different textures that made them passable in all weather conditions. That road system led not only to a more lively and prosperous trade route, but also to faster movement of military units in the event of raids or military aggression.

The road from Trier to Cologne was part of the Via Agrippa and is depicted on the Tabula Peutingeriana, a 12th century copy of a third-century map showing the Roman world road system. That road passed through several small villages as well as sanctuaries, police stations, hostels, military garrisons and vici 8(the plural of vicus), including Bonn13.

Remains of Hypocaust Heating System

This find, which was made during canal works, is special on the one hand because it is particularly well preserved, but on the other hand it is hardly surprising. The area where the heating system (hypocaustum) was found is very likely to have been inhabited along the foot of the mountain. The location is favourable: close to the road to Koblenz and not too far from the vicus. The underfloor heating, which was situated under an apse, most probably belonged to baths. This could have been the villa of a wealthy citizen (possibly a war veteran?) who did not want to renounce Roman luxury.

After the canal work, the hollow space was filled with a special material to prevent the site from sinking. This material can easily be removed for future excavations.

Links

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/images/outreach/roman-bonn/rheinaue-matronae-2.jpg

- https://landesmuseum-bonn.lvr.de

- https://www.roemer.nrw/en/roman-province-lower-germania

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#SlavesandFreedmen

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#Heerstrasse

- https://www.worldccbonn.com/en/

- https://youtu.be/c2OsdDKvF_E?si=NsL1ZMA2SxudeAjq&t=11

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#localpopulation

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#EpitaphofEuthenia

- https://www.hdg.de/en/haus-der-geschichte

- https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Streifenhaus_(r%C3%B6misch)#/media/Datei:Rekonstruktionszeichnung_mehrerer_Streifenh%C3%A4user.jpg

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#RomanBathsMarriott

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#MilitaryPresence

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Mercury-Roman-god

- https://db.edcs.eu/epigr/epi_ergebnis.php

- https://www.bonner-muenster.de/

- https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WMVJ97_Martinstafeln_am_Bonner_Mnster_Bonn_NRW_Germany

- https://www.stadtwerke-bonn.de

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#Stiftsplatz

- https://www.britannica.com/technology/hypocaust

- https://bodendenkmalpflege.lvr.de/de/ueber_uns/aussenstellen/as_overath.html

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#Southerngate

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#SoldiersandCitizenship

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17079

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#TrachyteBlocks

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/430/

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#Aldi

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kennedy_Bridge_(Bonn)

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Medusa-Greek-mythology

- https://landesmuseum-bonn.lvr.de/de/index.html

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn#TradeExchangeResources

- https://www.academia.edu/44517466/Ristow_2015_The_Dietkirche_at_Bonn_archaeology_and_history_of_late_antique_and_early_medieval_Bonn_Die_Dietkirche_in_Bonn_Arch%C3%A4ologie_und_Geschichte_ihrer_Fr%C3%BChzeit

- https://books.google.de/books?id=jCrp7ZC6M48C&printsec=frontcover&hl=de&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/3678976.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A3acb4dd683bad0fd34a461a2a92c5f33&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/44425305

- https://www.kuladig.de/Objektansicht/KLD-288987

- https://brill.com/display/book/9789047444299/Bej.9789004179998.i-422_007.xml

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#BakingOven

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#PotteryWorkshop

- https://www.iak.uni-bonn.de/de/institut/abteilungen/klassische-archaeologie/klassischearchaeologie

- https://ga.de/ga-english/news/researchers-puzzled-over-dancing-little-man_aid-99578525

- https://www.lg-bonn.nrw.de/beh_sprachen/beh_sprache_EN/10_About_us/160_History_of_the_Landgericht/index.php

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drachenfels_(Siebengebirge)

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#Koenigswinter

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/en/outreach/roman-bonn-site-descriptions#crane

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Annia-Galeria-Faustina

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Trajan

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hadrian

- https://www.dependency.uni-bonn.de/images/outreach/roman-bonn/drachenfels.jpg

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siebengebirge

- https://apx.lvr.de/en/roemische_stadt/roemische_stadt.html

- https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/292/

- https://www.roemer.nrw/en/bonn-cluster-kottenforst-sud

- https://vici.org/vici/15015/?lang=de